From Prompts to Habitats: 3 principles for effective agents

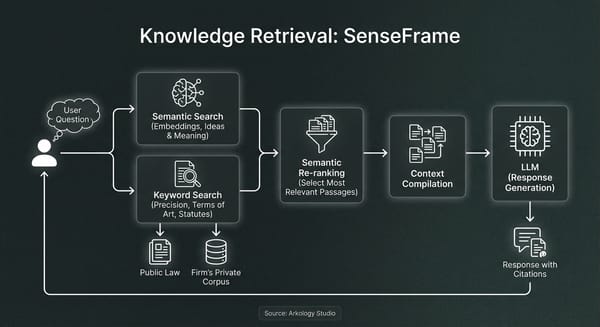

For the last few years, many have come to know “AI” as essentially a conversational partner: we prompt the model, it responds, we repeat. This simple prompt-response pattern in LLMs enables everything from knowledge support chatbots, summarization and drafting tools, semantic search over documents, and early code assistants. In these interactions, you are leading the conversation, and the quality of the AI’s response is largely the result of your conversational ability. This is why prompt engineering, the craft related to prompt design and optimisation, has become an important part of getting good results out of early LLM-based AI systems.

But, what if we’d like the AI to work on its own, and only ask us questions when it needs clarity or direction? We’re now entering the domain of “agentic AI”: systems that operate autonomously, make decisions, and take actions based on their goals. Here, high-level goals such as “read all the documents pertaining to this legal matter and draft a case for court” or “review the existing knowledge retrieval infrastructure, identify areas for improvement, then implement the changes”, must be broken down into sub-tasks, dependencies identified, and changes validated in order to reliably make progress toward the end goal—ideally with minimal human oversight. As is expected, these kind of tasks are simply outside the scope of the simple prompt-response pattern.

Our experience with early versions of coding ‘agents’ provide an illuminating example of trying to make the prompt-response pattern semi-autonomous: the AI would frequently forget its primary task, go on long-winded coding sprees, and confidently hallucinate solutions to problems that didn’t exist. I’ve heard it described as ‘babysitting a highly capable junior developer with amnesia’. I don’t think that’s too far off. The problem, of course, isn’t that the model is unintelligent. It’s that intelligence isn't found only in the model weights themselves.

Expanding AI's Cognitive Lightcone

Agency grows when perception, action, and evaluation are coherently coupled across time.

One way to understand the capability of agentic systems is through the work of Michael Levin, a developmental biologist who studies agency and cognition in living, designed and hybrid systems. Levin argues that agency is not binary, but graded, and that every agent has a cognitive light cone: the scale of space, time, and abstraction over which it can reliably pursue goals.

Biological agents routinely fail when asked to solve problems outside their light cone. A single cell cannot plan an organism; a tissue cannot reason about an ecosystem. But within their cone, these systems are remarkably robust—able to adapt, self-correct, and achieve stable outcomes when perturbed.

Artificial agents behave in similar ways. If you ask an agent for goals outside its cone—“run my company,” “fix the legal system”—you get proxy behaviours, drift, and confident nonsense. But if you ask for goals within its cone—“draft this memo with citations,” “run these checks,” “produce this artefact”—you can get reliable results, because the environment provides grounding and verification.

From this perspective, designing more capable AI agents is partly about expanding their cognitive light cones. Not by making models larger per se, but by extending the loops they can stably close: richer environments, better tools, longer-lived artefacts, clearer feedback, and tighter verification. As with biological systems, agency grows when perception, action, and evaluation are coherently coupled across time. For Levin, agency is already present in living systems across scales. Rather than thinking about designing 'systems that behave intelligently', we can think about how to shape the conditions under which intelligence can stably express itself.

What’s becoming clear—both in the field and in our own work at Arkology Studio—is that capable agents need at least three things to establish a cognitive lightcone capable of reliably pursuing goals beyond what basic LLM-based systems have already achieved. Call them loops, environments, and artefacts.

1) The Agentic Loop

If the prompt-response pattern is like a simple chemical reaction, an agentic loop is more akin to metabolism: a self-sustaining regulatory process that keeps the agent aligned with a desired outcome:

Gather context → take action → verify → repeat.

This agentic loop—now explicitly articulated in frameworks like Anthropic’s Claude Agent SDK—functions like a living regulatory cycle: a continual process of sensing, acting, verifying, and adjusting that keeps goals viable by repeatedly bringing intention back into contact with the model's reality (e.g. its compute/simulated environment, original prompt, etc.).

- Gather context: search the workspace, locate relevant files, recover prior decisions, inspect logs or artefacts.

- Take action: edit files, generate scripts, run commands, call APIs, produce intermediate outputs.

- Verify: run tests, lint, validate against schemas, render and screenshot, perform a second-pass check.

- Repeat: adjust based on feedback until constraints are satisfied.

The kinds of AI systems emerging now that are capable of executing complex workflows end-to-end without major intervention from a human overseer are ones where this agentic loop can run with fewer dead ends.

2) Artefacts: external memory

In a single prompt–response interaction, there’s no memory beyond what you keep re‑feeding the model. Time is collapsed, and consequently, so is the agent’s cognitive lightcone. Agentic systems escape that trap by producing and using artefacts such as checklists, scripts, logs, intermediate outputs, commits, generated tables. These artefacts carry the agent's intent forward through time. By leaving traces of thought, intention and progress, they become part of the agent’s cognition.

This mirrors what philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers described as the extended mind: the idea that cognition does not stop at the skull, but is distributed across tools, notes, symbols, and environments that reliably participate in thinking. A notebook, a diagram, or a checklist aren’t simply ‘tools’ for thinking—they are part of the thinking process.

Agentic AI systems work the same way. When an agent writes a script, saves a plan, or leaves a progress log, it is offloading cognition into the environment so it can be picked up later—by itself, or by another agent. Memory is no longer something that has to be squeezed into a context window; it is enacted through stable artefacts that persist across time.

This is also where Skills—as introduced in systems like Claude—start to make sense. A skill, at its best, is procedural knowledge packaged with the means to execute it: instructions, resources, and often scripts, stored in a predictable structure that an agent can discover and load when needed. In biological terms, skills resemble genetic instructions: compact programs that don’t specify every outcome in advance, but reliably shape behaviour when expressed in the right environment. In cultural terms, they resemble practices: learned ways of doing things that can be transmitted, adapted, and recombined.

Seen this way, skills are transferable, loadable cognitive bundles. They allow agents to carry not just information, but ways of acting across contexts and time—making organisational know-how executable without baking it into the model itself.

3) Environment: computational medium

So, where do these artefacts ‘live’ and where do the 'agentic loops' express themselves? In nature, cognition is coupled to the biological agent's environment: it senses, it internalizes/models what it senses, and then it acts—oftentimes changing the environment in turn. Similarly, AI agents need an environment through which to instantiate and express themselves. If there’s one takeaway from this section, it's that ‘the agent’ and ‘its environment’ need to be considered as part of an integrated system.

Step into any knowledge worker’s office and notice how their environment: the desk, file cabinets, scratch pads, library, smartphone/laptop – are integral to the way in which they work. Similarly, effective agents need a computational environment they can arrange (and re-arrange) as needed. This might look like:

- a filesystem to create, edit and store durable artefacts

- a terminal to do real operations

- A search system to locate relevant information/artefacts

- concrete ways to verify output

Emerging frameworks such as OpenAI's AgentKit and Claude Agent SDK attempt to standardise a harness in which an agent can operate inside a manipulable environment: a scratchpad of sorts wherein the model can record its thoughts for future reference, utilise tools and talk to other models/services. The model is no longer expected to hallucinate competence. It’s expected to close the loop against reality—to search, act, check, and iterate inside a computational workspace until its work passes concrete constraints.

Toward Agent Habitats

It’s clear we’re moving away from treating intelligence as something that happens inside a large model, and toward understanding intelligence as a distributed process of goal-directed interaction with its environment. Loops help the agent reflect and verify its actions, artefacts help the agent transfer intention through time, while all of this occurs within a manipulable computational environment: all part of a unified cognitive fabric. AI agent cognition becomes a relational, reflexive process that cannot be isolated to just the model weights.

If prompt engineering was about asking better questions, the next phase is about designing agent habitats: environments within which intelligence can reliably emerge to pursue goals—persisting, self-regulating, adapting, and remaining accountable as work unfolds—perhaps in concert with other agents (more to come).

By Arkology Studio — purpose-led systems design & software engineering studio