Designing Coherent Interfaces Between Cybernetic Systems and Socio-Technical Organisms

Ontology, Meaning Fields, Relational Context, Pluralism and Provenance in Enterprise Intelligence

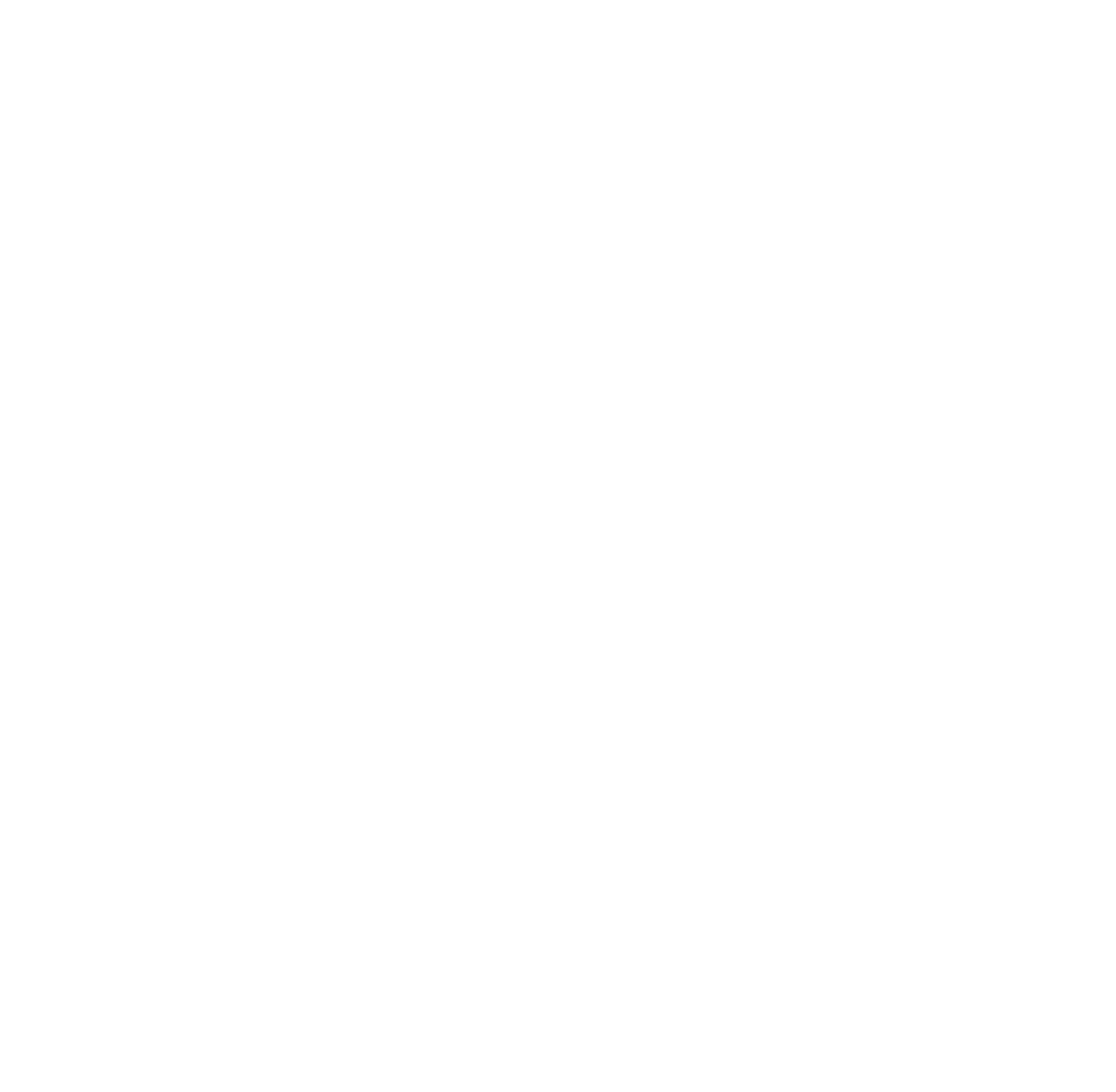

This essay develops a first-principles framing for how a cybernetic system—understood as a sensing, modelling, decision, and action loop—may interface coherently with a socio-technical organism such as a company and its surrounding ecosystem. The focus is not on product design, but on representational and epistemic prerequisites: how a system can (i) compute over organisational state, (ii) remain sensitive to meaning and context, and (iii) sustain traceability across time and sources, under conditions of plural perspectives and partial observability. This essay argues for a representational substrate composed of (1) a conceptual ontology (entities, relations, events), (2) a semantic “meaning field” (geometric representations), (3) explicit relational structure (knowledge graph), and (4) provenance and temporality (historical graph). Two living-systems anchors—stigmergic coordination in ant colonies and network optimisation in Physarum—are used not as metaphors of equivalence, but as concrete examples of intelligence that arises from coupling bounded agents to structured, writable environments over time.

This essay is written in conversation with process-oriented and systems-informed traditions that treat organisations as evolving rather than static. It is informed, in particular, by Gilbert Simondon’s attention to becoming and stabilisation, Gilles Deleuze’s emphasis on relational composition, Nora Bateson’s Warm Data sensibility regarding context and meaning, and Michael Levin’s work in developmental biology on morphogenesis and multi-scale regulation as a form of distributed, goal-directed problem-solving. These references are offered as orienting influences rather than as specialised terminology the reader must adopt.

1) Problem framing: cybernetics in a plural, evolving environment

A company is not merely a collection of data tables; it is a socio-technical organism constituted by heterogeneous agents (humans, software systems, institutional processes), operating within constraints and values, and interacting with an environment (customers, suppliers, regulators, partners). Its “state” is distributed across documents, databases, contracts, informal communications, and embodied practices. Any cybernetic system intended to interface with such an organism encounters several structural conditions:

- Partial observability: the system sees only what is recorded or accessible.

- Pluralism: different agents maintain differing, sometimes incompatible, perspectives on “what is happening”.

- Temporal drift: organisational reality changes; representations become stale.

- Heterogeneous evidence: facts, claims, narratives, and interpretations coexist.

- Value-ladenness: objectives and constraints are not neutral; they encode normative commitments.

Given these conditions, the central question becomes: what representational and epistemic structures make coherent interaction possible? The aim is not omniscient truth, but operational coherence: the capacity to produce outputs (decisions, actions, explanations) that reliably align with the organism’s constraints and produce beneficial consequences within its environment.

2) Representation as epistemology: what must be knowable, computable, and justifiable

What a system can do is bounded by what its representations make knowable and actionable.

In cybernetic terms, the interface problem is not primarily “how to generate text”, but how to support reliable loops of:

- Sensing (ingesting signals from the organism and environment),

- State estimation (constructing representations of relevant conditions),

- Control / decision (selecting actions under values and constraints),

- Actuation (calling tools, triggering processes), and

- Feedback (updating representations as outcomes occur).

A key proposition follows: the representational substrate determines the system’s epistemic capabilities. Certain questions require exact computation, others require semantic sensitivity, and most high-value organisational inquiries require both.

Why meaning alone is insufficient

Geometric semantic representations (embeddings) support similarity and associative retrieval, but they do not natively support many operations crucial to organisational reasoning: ranking by numeric attributes, aggregation, verification against constraints, and compositional queries (joins, filters, time-bounded statements). If the system must answer, for example, “Which contracts breach SLA thresholds most frequently?”, it requires structured access to time series, thresholds, and counts—not only proximity in a meaning field.

Why structure alone is insufficient

Conversely, purely structured databases fail to capture much of the organism’s “dark matter”: tacit commitments, exceptions, contextual narratives, contractual nuance, and historical rationales that live in documents and communications. Many organisational questions—especially those involving interpretation of policy, negotiation history, or operational exception handling—cannot be satisfied by tables alone.

This motivates a hybrid: a substrate that supports computation and meaning, and enables systems to move between them coherently.

3) A composite substrate: entities, relations and events, the meaning field, and provenance

A coherent interface requires both calculable state and interpretable context

Herein is proposed a conceptual substrate with four interlocking components. This is not a specific implementation, but a set of representational commitments that enable coherent cybernetic interfacing.

Conceptual ontology: entities, relations, events

The ontology is the system’s conceptual commitment about what exists within the organism’s operative membrane and how it composes. A minimal but expressive ontology typically requires:

- Entities: identifiable objects with persistence (employees, suppliers, products, contracts, tickets).

- Relations: structured links that contextualise entities (employed_by, supplies, governed_by, depends_on).

- Events: state transitions (contract signed, shipment delayed, incident resolved) that ground change over time.

This triad matters because each component supports a distinct epistemic operation: entities enable identity and reference, relations enable context and traversal, and events enable temporality, provenance, and causal inference (with caution).

Gilbert Simondon’s work is a useful orienting reference here, insofar as it encourages treating ‘entities’ not as timeless categories but as practical stabilisations within an evolving field. Applied modestly, this supports a representational stance in which organisational objects (such as suppliers, contracts, or incidents) are held as coherent identities only to the extent that they remain supported by ongoing practices, relations, and events. In this view, identity is maintained through coupling to its conditions—its operational context and history—rather than assumed as a fixed essence, which reinforces why relations and temporality are integral to the ontology rather than optional additions.

Semantic layer as a meaning field (geometric representation)

The semantic layer is a geometric space supporting associative access to relevant content and concepts. Importantly, this layer is most coherent when it is anchored to identity: each entity (and often each relation and event) has a canonical textual representation that can be embedded, enabling alignment between structured and semantic retrieval.

This meaning field does not replace structure; it complements it by retrieving what is difficult to formalise whilst preserving contextual relevance.

Relations as first-class citizens: knowledge graph structure

To move beyond isolated facts and snippets, relational structure must be explicit. A knowledge graph (or graph-like representation) enables the system to assemble context around any atom—whether discovered via structured computation or semantic retrieval—by traversing relevant relationships.

This emphasis on connection reflects a broader philosophical intuition: organisational structure is better understood as enacted than as given. It is constituted by recurrent patterns of relation—material dependencies, informational interfaces, institutional constraints, and normative commitments—that distribute agency and shape the space of possible actions; in Deleuze’s terms, the organisation is a multiplicity arranged as an assemblage, defined less by fixed properties than by the capabilities that emerge from its relations.

A crucial refinement is that relations come in at least two kinds:

- Foundational relations: definitional and relatively stable (employed_by, owns, located_in).

- Derived relations: constructed, perspectival, and time-sensitive (high_risk_supplier, strategic_account, compliance_concern).

Derived relations remain important, but they require explicit contextualisation: who asserted them, under what criteria, and over what time horizon. This is where pluralism becomes a representational requirement rather than a governance afterthought.

Provenance and temporality: towards a historical graph

Provenance is not “metadata”; it is the basis for epistemic responsibility. A system interfacing with a socio-technical organism must, at minimum, be able to represent:

- Source: where a claim or observation originated (system logs, documents, human input).

- Time: when it was true, asserted, or observed.

- Authority / role: who or what produced it (and their standing).

- Transformation lineage: how it was derived or summarised.

This implies a historical graph: entities and relations as they evolve through events, enabling the system to avoid conflating past state with present state, and to support inquiry into change (“what shifted, and when?”). Importantly, this is compatible with a coherence-based stance: provenance allows the system to represent uncertainty and disagreement without forcing premature singular truth.

4) A concrete organisational inquiry requiring the full substrate

Consider the question:

“Which three supplier constraints are most likely to cause missed deliveries in the next 30 days, and what is the lowest-cost intervention that preserves service-level commitments?”

This inquiry cannot be handled coherently by a single representational modality:

- It requires computation: delivery performance statistics, lead times, failure rates, costs, SLA thresholds.

- It requires meaning: contract clauses, exception handling, informal commitments, narrative context from incident reports and communications.

- It requires relational traversal: supplier → component → SKU → customer → SLA, including dependencies and substitution possibilities.

- It requires provenance and time: recent changes in supplier behaviour, newly negotiated clauses, outdated commitments, and recency-weighted evidence.

The conceptual significance of this example is not that it is “hard”, but that it is cross-representational. The system must not only retrieve information; it must orchestrate movement between semantic retrieval (to locate obligations, precedents, and contextual constraints), structured queries (to compute likelihoods and impacts), graph traversal (to assemble dependency context), and provenance checks (to weight and justify conclusions). Here the interface becomes cybernetic: the system estimates state, tests interventions against constraints, and proposes actions with traceable grounding.

5) Living-systems anchors: externalised memory and embodied network computation

The goal of the biological examples here is to point to concrete cases in which adaptive behaviour emerges from the coupling of bounded agents to structured environments. Read as orienting references rather than as literal models, they underline a familiar point in complex systems thinking and developmental biology: goal-directed regulation can arise from context, constraints, and distributed feedback, rather than from central representation alone; this theme is explored in contemporary work on morphogenesis and multi-scale regulation, including Michael Levin’s.

Ant colonies: stigmergy as externalised state and distributed computation

In ant colonies, coordination is often achieved via stigmergy: ants modify the environment (pheromone deposition), and subsequent ants respond to those modifications. Several properties are relevant:

- External memory: pheromone trails store state outside any individual ant.

- Temporal governance: pheromones decay; recency matters.

- Local rules, global coherence: individual ants follow local gradients, yet colony-level routing can approximate efficient paths and adapt to disruptions.

This offers a concrete model of how coherence can arise without centralised omniscience: by writing and reading from an environment that is structured, time-sensitive, and traversable. In organisational terms, a conceptual ontology coupled to a historical graph can be treated as a “writable habitat” where signals persist, decay, and are recomposed by agents over time.

Physarum (slime mould): network optimisation as embodied computation

Physarum polycephalum demonstrates a different but complementary form of distributed intelligence. It can form transport networks that balance efficiency and resilience relative to nutrient distributions. The computation is neither symbolic nor centralised; it is performed through the organism’s morphology coupled to environmental gradients.

Conceptually, this suggests an additional principle: some computations are best achieved by evolving structures rather than evaluating explicit plans. In organisational systems, relational structure (graphs) and derived relations can be treated as evolving morphological scaffolds that reflect current constraints, rather than as static representations.

Together, ant colonies and Physarum offer three disciplined insights: intelligence can be distributed and coupled to its environment; time and decay (or adaptation) are essential for coherence under change; and representational scaffolds can function as computational substrates beyond internal cognition.

6) Pluralism, evidence, and values: coherence as the governing aim

A socio-technical organism is not epistemically uniform. It contains conflicting interpretations, incentives, and narratives. A cybernetic interface that assumes singular truth risks either suppressing pluralism or manufacturing false certainty. A coherence-based approach instead treats knowledge as layered:

- Observations: logged events, measurements, transactions.

- Assertions: claims made by agents or systems (“supplier X is unreliable”).

- Interpretations: synthesised models or summaries derived from evidence.

This stance aligns with Nora Bateson’s Warm Data orientation, which foregrounds the interplay of contexts in producing understanding. On this view, what counts as an ‘observation’, an ‘assertion’, or a plausible ‘interpretation’ is shaped by domain and perspective, so the system must treat relevance as contextual rather than universal. This separation supports disciplined inquiry: which parts of the output are grounded in observation; which are contingent on who asserted what; and which are interpretive hypotheses.

Similarly, the system’s point of view is unavoidable. Goals, values, and risk tolerances shape what is optimised, what is ignored, and what counts as acceptable action. Rather than claiming neutrality, a rigorous framing treats values as constitutive parameters of the cybernetic loop.

Conclusion

A coherent interface between cybernetic systems and socio-technical organisms requires more than language generation. It requires a representational substrate that supports computation, meaning, relational context, and traceable evolution over time—whilst remaining honest about pluralism, partial observability, and embedded values. The proposed framing—conceptual ontology (entities, relations, events), semantic meaning field, knowledge graph traversal, and provenance-temporal scaffolding—does not guarantee correctness, but it establishes the conditions under which disciplined inquiry and reliable interaction become possible. Living systems such as ant colonies and Physarum illustrate that intelligence can reside in the coupling between bounded agents and structured, time-governed environments. The organisational challenge is to design analogous substrates—legible, writable, and evolvable—so that socio-technical organisms can be engaged with coherence rather than illusion.

If you want to build coherent AI systems that can work with real data, real constraints, and real organisational complexity, reach out — hello@arkology.studio

By Arkology Studio — purpose-led systems design & software engineering studio